It was the first of the 'Three Stories in the Style of Benson' stories (in The Hymn of the Universe) – ‘The Picture ‘- which was actually the starting point for conversation between Ian and myself. (See Here) I have tried to find other examples of meditations or reflections on sacred images – especially icons – but I have not come across anything as intense as what we read in his story. The story about ‘the picture’ is a truly remarkable description of how he saw beyond the image of the Sacred Heart and how it served as window or doorway into its deeper and profound meaning. What we read is not a kind of de-construction of the image of the Sacred Heart, but more a process of de-solving it. (READ STORIES HERE)

He describes his ‘friend’ – that is himself – as someone who ‘drank of life everywhere 'as at a sacred spring’. The story will tell us how ‘his friend’ came to see all the ‘power and multiplicity’ of the universe in Christ. And, how this vision of a universal Christ was the result of a gradual process, but how it had been punctuated by the light of ‘life-renewing intuitions’ which came like the raising of a curtain – in ‘jerks’.

It begins by reflecting on how an artist could possibly capture Christ if he were to appear before us as God and Man? How could an artist paint an image of Jesus? And as he is praying in front of a picture of Christ ‘offering his heart to men’ his friend experiences a vision. (Now the fact that he says it was Christ ‘offering his heart to men’ means that the picture of the Sacred Heart is of the Batoni type. )

Teilhard does not dissect the picture in an analytical way – we know that it did not really appeal to him – but instead he just allowed his eyes to ‘wander over the outlines of the picture’. This is a process not of de-constructing the image but allowing the image to dissolve. He allows the painting to melt by ‘relaxing’ his ‘visual concentration’. This suggests that the vision was the result of method: a deliberate withdrawing of analytical perception. He wants to see beyond the ‘lines’ which were ‘sharply defined’. Another way of saying this is that he opens his heart to the Sacred Heart. ( In The Divine Milieu, written in 1927, he describes this as seeing through the light of purity, faith, and fidelity.)

If we think about this, letting an image melt or dissolve is actually the opposite of what we do when we are trying to make sense of an image: we focus on line and detail. We step forward and look intensely at the detail. But Teilhard is responding to the picture as if it were an impressionist painting. He is stepping back and trying so see the image as a whole. He is trying to see the image not as real or as an object or collection of parts and elements but as a whole. He is trying to see beyond the image as art. If we read what he says in his essay on the evolutionary function of art, it appears that he is turning the Batoni into the opposite of art. He is returning back to nature! In nature, he says, the supreme art we find in ‘fish , the bird the antelope’ appears as a ‘luminous fringe around every form…as soon as the realization attains perfection in its expression’. ( 88) Human art involves things ceasing to be a ‘fringe’ and becoming objective. Before his eyes Batoni’s picture ceases to be an object and melts back into a ‘luminous fringe’. Lines dissolve and the ‘edge which divided Christ from the surrounding world changes into a layer of 'vibration' in which all 'delimitation was lost.’ There is a logic in his vision, for the first thing to melt is the outline of the figure, and then the rest of the image melts away. The dividing line which separates Christ from the rest of the cosmos dissolves: ‘ It was as though the planes which marked off the figure of Christ from the world surrounding it were melting into a single vibrant surface whereon all demarcations vanished.’

What he sees is a process of metamorphosis which begins with the lines which separate Christ’s body in the picture and then begins to flow through the picture – inwardly : from the lines of demarcation to the inner core of the image.

‘First of all I perceived that the vibrant atmosphere which surrounded Christ like an aureole was no longer confined to a narrow space about him, but radiated outwards to infinity. Through this there passed from time to time what seemed like trails of phosphorescence, indicating a continuous gushing-forth to the outermost spheres of the realm of matter and delineating a sort of blood stream or nervous system running through the totality of life.

‘The entire universe was vibrant! And yet, when I directed my gaze to particular objects, one by one, I found them still as clearly defined as ever in their undiminished individuality.

Thus Teilhard shifts from seeing Christ as universal – radiating through the totality of life – back into seeing Christ in particular or objective way. Christ is universal – cosmic – but he is also deeply personal. Christ has a centre. And this centre is the very centre of a vibrating universe. He sees the universe vibrating with energy radiating from Christ. And, in opening his heart to Christ he feels and experiences these vibrations. Heart speaks to heart.

All this movement seemed to emanate from Christ, and above all from his heart. And it was while I was attempting to trace the emanation to its source and to capture its rhythm that, as my attention returned to the portrait itself, I saw the vision mount rapidly to its climax.

This climax is a vision or experience of the Sacred Heart as the Transfiguration on a cosmic scale. Christ’s garments are woven from the very fabric of matter, space and time. The Sacred Heart is becoming the universe. Christ is filling, shaping and energizing the entire universe:

Christ’s garments…had that luminosity we read of in the account of the Transfiguration; but what struck me most of all was the fact that no weaver’s hand had fashioned them — unless the hands of angels are those of Nature. No coarsely spun threads composed their weft; rather it was matter, a bloom of matter, which had spontaneously woven a marvellous stuff out of the inmost depths of its substance; and it seemed as though I could see the stitches running on and on indefinitely, and harmoniously blending together in to a natural design which profoundly affected them in their own nature.

And although the focus of the vision is the heart, it is Christ's eyes which seem to command Teilhard's attention and bring the piece to a conclusion.

Over the glorious depths of those eyes there passed in rainbow hues the reflection — unless indeed it were the creative prototype, the Idea—of everything that has power to charm us, everything that has life. ....And the luminous simplicity of the fire which flashed from them changed, as I struggled to master it, into an inexhaustible complexity wherein were gathered all the glances that have ever warmed and mirrored back a human heart…Now while I was ardently gazing deep into the pupils of Christ's eyes, which had become abysses of fiery, fascinating life, suddenly I beheld rising up from the depths of those same eyes what seemed like a cloud, blurring and blending all that variety I have been describing to you. Little by little an extraordinary expression, of great intensity, spread over the diverse shades of meaning which the divine eyes revealed, first of all permeating them and then finally absorbing them all…And I stood dumbfounded.

And it is Christ's eyes that reminds him of the eyes of a dying soldier. At the end, the painting returns to its 'precise definition and its fixity of feature'.

The story is an attempt to get us to look at the Sacred Heart in a very different way: to look through and beyond the image. We have to imagine it as the core of an energy of love which spreads out throughout the universe and which weaves all things together in a universal fabric of which we are a part. It is an attempt to communicate a vision of Christ who is holding all things together which we have to see in that heart which is being offered in Botoni’s painting. What Teilhard wants us to see in the Sacred Heart is the transfiguration and metamorphosis of the Sacred Heart - what will become for him in due course, the 'universal Christ' 'divine milieu' and ultimately 'Christ Omega'.

As one reads the story it becomes almost impossible to imagine how any artist could represent Teilhard's vision. We only have two references by Teilhard to images or pictures which illustrate in some way what this story tries to convey. The first is in the Divine Milieu - written in 1927 and the second illustration is the picture of the Sacred Heart by Henri Pinta on which he wrote his litany.

In the Divine Milieu he explores the 'nature of the Divine Milieu' as the 'universal Christ' in terms of a process in which God 'enfolds us' and 'penetrates us by creating and preserving us'. It is a process of 'unitive transformation' as revealed by St. Paul and St John. It is the ' quantitative repletion and the qualitative consummation of all things'. (122) What we see in this story therefore is Teilhard's early attempt to express how he was experiencing God in this way: as an dynamic organizing force that energies and animates the universe. The story is trying to paint a picture in words of what this universal Christ feels like or could look like.

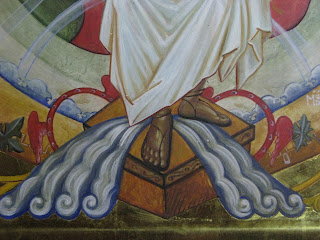

As we contemplate the Sacred Heart - either by using a 'traditional' image or this icon, what we are being asked to explore is the way that:

Christ does not act as a dead or passive point of convergence, but as a centre of radiation for the energies which lead the universe back to God through his humanity, the layers of divine action finally come to us impregnated by his organic energies. ( Divine Milieu, Torchbook, p123)

As Teilhard contemplates the Sacred Heart this is what he sees: 'a centre of radiation' leading us and the universe back to God through the humanity of Christ. This section of the The Divine Milieu concludes with this image of Christ.

Disperse, O Jesus, the clouds with your lightning! Show yourself to us as the Mighty, the Radiant, the Risen! Come to us once again as the Pantocrator who filled the solitude of the cupolas in the ancient basilicas! Nothing less that this Parousia is need to counter-balance and dominate in our hearts the glory of the world that is coming into view. And so that we should triumph over the world with you, come to us clothed in the glory of the world. (Divine Milieu, Torchbook, )

|

| Christ Pantocrator by Ian Knowles at Elias Icons |

Thus we can read this story as Teilhard's exploration of Christ Pantocrator - ruller of all. Christ - Pantocrator. But in which case we might suppose that Teilhard would have actually chosen an icon of Christ Pantocrator to sit on his desk. But I can find no reference to any such icon in his possession. The reason for this is that he thought the image of Christ as the Pantocrator we find in St. Paul and St John was better represented by the Sacred Heart, for all its shortcomings. His Pantocrator has a heart which represents the dynamic beating and pulsing of divine energy: a heart as the 'foyer ', axis, pole or centre of the universe. Hence the image which he thought best captured what he experienced and what he saw in Sacred Heart was the Pinta picture as it was for him 'a quite simple illustration' of ' a vague representation of the universal “foyer” of attraction .' And it is the Pinta image he had on his desk and which he treasured, and not a Byzantine icon of Christ Pantocrator.

The Sacred Heart for Teilhard is a powerful focus - or foyer - which can be used to direct our thoughts to the presence of the divine in us and all around us. It was a image, however, that has to be contemplated through the eyes of faith. In the Divine Milieu Teilhard returns back to Benson's stories.

The Sacred Heart for Teilhard is a powerful focus - or foyer - which can be used to direct our thoughts to the presence of the divine in us and all around us. It was a image, however, that has to be contemplated through the eyes of faith. In the Divine Milieu Teilhard returns back to Benson's stories.

In one of his stories, Robert Hugh Benson tells of a 'visionary ' coming on a lonely chapel where a nun is praying. He enters. All at once he sees the whole world bound up and moving and organising itself around that out-of- the-way spot, in tune with the intensity and inflection of the desires of that puny, praying figure. The convent chapel had become the axis about which the earth revolved. The contemplative sensitised and animated all things because she believed; and her faith was operative because her very pure soul placed her near to God. This piece of fiction is an admirable parable. The inward tension of the mind towards God may seem negligible to those who try to calculate the quantity of energy accumulated in the mass of humanity. And yet, if we could see the 'light invisible ' as we can see clouds or lightning or the rays of the sun, a pure soul would seem as active in this world, by virtue of its sheer purity, as the snowy summits whose impassable peaks breathe in continually for us the roving powers of the high atmosphere. (Divine Milieu, Torchbook, 133)

In his story it is the Sacred Heart which is the axis which enables him to see ' the light invisible. But …We have to look at the image of the Sacred Heart with a pure heart and with faith in that axis. The mystery of the Sacred Heart can only be grasped when we see the world with a pure heart and with faith and with fidelity. If we are to be open to radiating energy of love from the Sacred Heart we have to be faithful and loyal to our quest to know God – through all the trials of our daily life.

Because we have believed intensely and with a pure heart in the world, the world will open the arms of God to us. It is for us to throw ourselves into these arms so that the divine milieu should close around our lives like a circle. That gesture of ours will be one of an active response to our daily task. Faith consecrates the world. Fidelity communicates with it. (Divine Milieu, Torchbook137-8)

In other words, we just don’t pray in front of the Sacred Heart and ‘bang’, we get it. In order to see the Sacred Heart in the way Teilhard saw it we have to realize that it takes work, effort and action on our part. If we wish the Sacred Heart to close around us like a circle, if we desire for our heart to become one with his – our centre to be within the divine centre – we have to find God’s love in every moment of our day. We have to make God’s love real in our lives and never keep our eyes off it. We have to seek a pure heart and live a life of faith, but we must keep our eyes on the Sacred Heart through all the ups and downs. He likens fidelity to the journey of the Magi. The light we follow is nor a fixed point in the universe. God is not static in our lives. God is ‘eternal discovery’ . God is a ‘moving centre’. And that star may appear at any time or place in our lives and like the Magi we must follow it.

Under the converging action of these three rays – purity, faith and fidelity – the world melts and folds. ( Divine Milieu, Torchbook, 139)

In the story of ‘ The Picture’ what we read is a poetic and mystical exploration of the meaning of the Sacred Heart. It was an early writing (1916) but in so many ways Teilhard was to spend the rest of his life following the glowing fire he saw in the Sacred Heart as a young man - and which possibly the story records. As I reflect on the image of the Sacred Heart in this icon I realize that we are all called to heed the call to follow this flaming star. The Sacred Heart has to become the axis around which our lives are centered.